Bloom filter for Scala, the fastest for JVM

TL;DR

My implementation of Bloom filter in Scala. The source code on github

The fastest implementation for JVM. (Take me straight to the benchmarks)

Zero-allocation and highly optimized code.

No memory limits, therefore no limits to the number of elements and false positive rate.

Extendable: plug-in any hash algorithm or element type to hash.

Yes, it uses sun.misc.unsafe ![]()

Intro

“A Bloom filter is a space-efficient probabilistic data structure that is used to test whether an element is a member of a set. False positive matches are possible, but false negatives are not. In other words, a query returns either “possibly in set” or “definitely not in set”. Elements can be added to the set, but not removed,” says Wikipedia.

What’s Bloom filter in a nutshell:

- Optimization for memory. It comes into play when you cannot put whole set into memory.

- Solves the membership problem. It can answer one question: does an element belong to a set or not?

- Probabilistic (lossy) data structure. It can answer that an element probably belongs to a set with some probability.

I find the following post quite comprehensive - “What are Bloom filters, and why are they useful?” by @Max Pagels. I couldn’t do it better, take a look if you aren’t familiar with Bloom filters.

Why yet another Bloom filter?

Because available ones suck! ![]() They don’t suit your needs because of performance or memory limitations. Or you just know that you can do it better. Frankly, neither is true. The reason is that you just get bored sometimes. (theme song)

They don’t suit your needs because of performance or memory limitations. Or you just know that you can do it better. Frankly, neither is true. The reason is that you just get bored sometimes. (theme song)

The major reason is performance. Working on high-performance and low latency systems, you don’t want to see that you are slow because of an external library and it allocates more than your code does. You want to focus on your business logic and have the dependencies you rely on to be as efficient as possible.

Another reason is memory limitations. All of them have size limitation caused by JVM array size limit. In JVM, arrays use integers for indexes, therefore the max size is limited by the max size of integers which is 2 147 483 647. If we create an array of longs to store bits then we can store 64 bit * 2 147 483 647 = 137 438 953 408 bits. This takes ~15 GB of memory. You can put ~10 000 000 000 elements with 0.1% probability into this Bloom filter. This is more than enough for most software. But when you work with Big Data such as web URLs, banner impressions, Real-time bidding requests, or any stream of events and Machine learning, then 10 billion elements is just the beginning. Sure, you can have workarounds for that: multiple Bloom filters, distribute them across multiple nodes, design your software to fit this limitation, but those workarounds aren’t always efficient, can be pricey or don’t fit into your architecture.

Let’s take a look at some of the available solutions.

Google’s Guava

Guava is a high quality core library from Google which contains such modules as collections, primitives, concurrency, I/O, caching, etc. And it has the Bloom filter data structure. Guava is the default option to start with for me. It’s battle-tested and works as expected. It’s fast. But…

Surprisingly, it allocates! I used the Google’s Allocation Instrumenter to print out all allocations. The following allocations happened for a check whether a 100 symbols string present in a Bloom filter or not. Here’s the list:

I just allocated the object [B@39420d59 of type byte whose size is 40 It's an array of size 23

I just allocated the object java.nio.HeapByteBuffer[pos=0 lim=23 cap=23] of type java/nio/HeapByteBuffer whose size is 48

I just allocated the object com.google.common.hash.Murmur3_128HashFunction$Murmur3_128Hasher@5dd227b7 of type com/google/common/hash/Murmur3_128HashFunction$Murmur3_128Hasher whose size is 48

I just allocated the object [B@3d3b852e of type byte whose size is 24 It's an array of size 1

I just allocated the object [B@14ba7f15 of type byte whose size is 24 It's an array of size 1

I just allocated the object sun.nio.cs.UTF_8$Encoder@55cb3b7 of type sun/nio/cs/UTF_8$Encoder whose size is 56

I just allocated the object [B@497fd334 of type byte whose size is 320 It's an array of size 300

I just allocated the object [B@280c3dc0 of type byte whose size is 312 It's an array of size 296

I just allocated the object java.nio.HeapByteBuffer[pos=0 lim=296 cap=296] of type java/nio/HeapByteBuffer whose size is 48

I just allocated the object [B@6f89ad03 of type byte whose size is 32 It's an array of size 16

I just allocated the object java.nio.HeapByteBuffer[pos=0 lim=16 cap=16] of type java/nio/HeapByteBuffer whose size is 48

I just allocated the object 36db757cdd5ae408ef61dca2406d0d35 of type com/google/common/hash/HashCode$BytesHashCode whose size is 16

This is 1016 bytes!! Just think about, we calculate a hash number of a short string and check whether the relevant bits are set, and it allocates ~1Kb of data. This is A LOT!! You could argue that allocations are cheap. Yes, they are, and you, most probably, won’t see an impact in isolated micro-benchmarks, but in production environment it gets much worse: it can stress the GC, lead to slow allocation paths, trigger the GC, lead to higher latency etc.

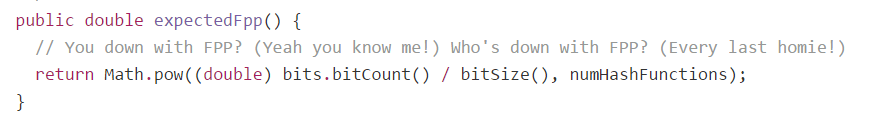

Anyway, it was fun to review the code. Sometimes you can find some nice Easter eggs there. For example this one here:

These lines are from the “O.P.P.” song by “Naughty by Nature” rap group which was very popular in the early 1990s. You have that subtle contact with the developer who wrote the code. He’s probably in his late 40s or early 50s at the moment (or was it she?). (“Disturbed” is probably over by this moment. Enjoy the old school rap bits)

Twitter’s Algebird

“Abstract algebra for Scala. This code is targeted at building aggregation systems (via Scalding (Hadoop) or Apache Storm).” It’s functional, immutable, monadic and very slooooow!! It supports only String as the element type. Yeah, string is the universal data format, you can store everything there ![]()

It uses loved by everyone MurmurHash3 which seems to be the best general purpose hashing algorithm. It takes 128-bit hash code and splits it to four 32-bit numbers. Then it sets one bit for each 32-bit number but not for the whole calculated hash. Which is quite controversial decision. I performed some rough tests and it turned out that Twitter’s Bloom filter has 10% more false positive responses than mine.

Digging deeper, what’s interesting is that Twitter’s Bloom filter uses EWAHCompressedBitmap under the hood which is a compressed alternative to BitSet. It’s an optimization for memory and very useful when you have sparse data. Say, you have bits starting at position 1 000 000, EWAH can optimize the set and won’t allocate space for leading zeroes. Intersections, unions and differences between sets will be faster in this case too. But random access is slower. Even more, the whole goal of hashing is to have uniform distribution of hash numbers and as even as better. These two points eliminate all advantages of using compressed bitsets. I did few tests to check total allocated memory, as a result Twitter’s Bloom filter allocated even more memory than my Bloom filter. Again, quite controversial solution in my opinion.

I wish I haven’t checked allocations, I won’t post the list of all of them because it’s pretty long. Allocations for the 100 symbol string check are 1808 bytes. ![]()

Yes, it’s functional, immutable, uses persistent data structures, monads, but that’s not the price to pay for it. Getting ahead of myself, I will say it’s performance is 10 times worse for reads and 100x for writes than the Bloom filter implemented by me.

ScalaNLP’s Breeze

“Breeze is a generic, clean and powerful Scala numerical processing library… Breeze is a part of ScalaNLP project, a scientific computing platform for Scala.”

That sounds interesting, like a fresh wind. But… There’s a surprise lurked inside. It takes a hash code of the object. “WAT?? Where’s beloved MurmurHash3?” you ask. It’s used only for “finalizing” the object’s hash. Yeah, it works with any type out-of-the-box but if you don’t know that little nuance you are done with large datasets.

And again, allocations - 544 bytes this time. Reviewing the code, you can encounter Scala-specific issues like the following one:

for {

i <- 0 to numHashFunctions

} yield {

val h = hash1 + i * hash2

val nextHash = if (h < 0) ~h else h

nextHash % numBuckets

}

It looks pretty neat: for comprehension, lazy evaluation, nice DSL. But it compiles to the following Java code which isn’t that nice and allocates a lot: intWrapper(), RichInt, Range.Inclusive, VectorBuilder and Vector, boxing and unboxing and so forth:

return (IndexedSeq)RichInt$.MODULE$.to$extension0(Predef$.MODULE$.intWrapper(0), numHashFunctions()).map(new Serializable(hash1, hash2) {

public final int apply(int i)

{

return apply$mcII$sp(i);

}

public int apply$mcII$sp(int i)

{

int h = hash1$1 + i * hash2$1;

int nextHash = h >= 0 ? h : ~h;

return nextHash % $outer.numBuckets();

}

public final volatile Object apply(Object v1)

{

return BoxesRunTime.boxToInteger(apply(BoxesRunTime.unboxToInt(v1)));

}

public static final long serialVersionUID = 0L;

private final BloomFilter $outer;

private final int hash1$1;

private final int hash2$1;

public

{

if(BloomFilter.this == null)

{

throw null;

} else

{

this.$outer = BloomFilter.this;

this.hash1$1 = hash1$1;

this.hash2$1 = hash2$1;

super();

return;

}

}

}

, IndexedSeq$.MODULE$.canBuildFrom());

Pretty scary! I think you got the point ![]() Let’s take a look at the solution used by me.

Let’s take a look at the solution used by me.

How does it work?

All that being said, I’ve reimplemented the Bloom filter data structure. You can find the source code on github. It’s available via the maven repository package:

libraryDependencies += "com.github.alexandrnikitin" %% "bloom-filter" % "0.3.1"

Here’s an example of its usage:

import bloomfilter.mutable.BloomFilter

val expectedElements = 1000

val falsePositiveRate = 0.1

val bf = BloomFilter[String](expectedElements, falsePositiveRate)

bf.add("some string")

bf.mightContain("some string")

bf.dispose()

Unsafe

One important thing is that it uses sun.misc.unsafe package underneath. It uses it to allocate a chuck of memory for bits. So that you have to dispose the Bloom filter instance and the unmanaged memory it allocated. Also it uses usafe for some tricks to avoid allocations, e.g. to get access to a private array of chars.

The type class pattern

The implementation is extensible and you can plug-in any hashing algorithm for any type. It’s implemented via the type class pattern. If you aren’t familiar with it then you can read about the pattern in @Daniel Westheide’s “The Neophyte’s Guide to Scala” blog post.

Basically, all you need is to implement the CanGenerateHashFrom[From] trait which looks like this:

trait CanGenerateHashFrom[From] {

def generateHash(from: From): Long

}

It’s invariant, unfortunately. I wish I could make it contravariant but the Scala compiler cannot properly resolve contravariant implicits. But there’s a hope, the feature is in the Dotty’s roadmap which is great!

By default, it provides a generic implementation of the MurmurHash3 hashing algorithm which is the best general purpose hashing algorithm. I’ve implemented the algorithm in Scala and it turned out to be faster than Guava’s, Algebird’s or Cassandra’s one. (I hope I didn’t make any mistakes ![]() ) Out of the box, the library provides implementations for

) Out of the box, the library provides implementations for Long, String and Array[Byte] types. As a bonus, there’s the 128-bit version of it for unlimited uniqueness ![]()

Zero-allocation

This Bloom filter implementation doesn’t allocate any object. The code is heavily optimized. I plan to write a separate post about the optimizations. Stay tuned ![]() Also there’s few unsafe tricks implemented to achieve that. Here’s the implementation of the

Also there’s few unsafe tricks implemented to achieve that. Here’s the implementation of the CanGenerateHashFrom trait for the String type:

implicit object CanGenerateHashFromString extends CanGenerateHashFrom[String] {

import scala.concurrent.util.Unsafe.{instance => unsafe}

private val valueOffset = unsafe.objectFieldOffset(classOf[String].getDeclaredField("value"))

override def generateHash(from: String): Long = {

val value = unsafe.getObject(from, valueOffset).asInstanceOf[Array[Char]]

MurmurHash3Generic.murmurhash3_x64_64(value, 0, from.length, 0)

}

}

It uses the unsafe.objectFieldOffset() method to take an offset of the “value” field which is an array of chars underneath an instance of the string class. Then it uses the unsafe.getObject() method to access the char array and passes it to the generic MurmurHash3.

Unfortunately, 128-bit version allocates one object. I hesitate between the (Long, Long) tuple and the ThreadLocal field. There’s no difference in synthetic benchmarks. Any opinions here? I hope I will see value types in JVM during my devlife. There’s a great attempt to get that done by @Gil Tene called ObjectLayout.

Limitations

As you might noticed already, there are some limitations. CanGenerateHashFrom[From] trait is invariant and it doesn’t allow to fallback to the object’s hashCode() method. You need to implement the hash function for your types by yourself. But I believe, it’s a reasonable price to pay for performance.

It won’t work on all JVMs because of “unsafe” package. And there’s no fallback implemented.

Can I use it from Java?

Yes you can. Unfortunately, it won’t be as nice as in Scala but you got used to it, uh? There are no implicits and the Java compiler won’t help you with them. Integration with Java is ugly in some parts but it works.

import bloomfilter.CanGenerateHashFrom;

import bloomfilter.mutable.BloomFilter;

long expectedElements = 10000000;

double falsePositiveRate = 0.1;

BloomFilter<byte[]> bf = BloomFilter.apply(

expectedElements,

falsePositiveRate,

CanGenerateHashFrom.CanGenerateHashFromByteArray$.MODULE$);

byte[] element = new byte[100];

bf.add(element);

bf.mightContain(element);

bf.dispose();

Benchmarks

We all love benchmarks, right? Exciting numbers in a vacuum, they are so attractive. If you ever decide to write benchmarks then use JMH please. It’s a Java library created by @Aleksey Shipilev “for building, running, and analyzing nano/micro/milli/macro benchmarks written in Java and other languages targeting the JVM.” There’s a neat sbt plugin on github by @Konrad Malawski.

Here’s a benchmark for the String type and results for other types are very similar to these:

[info] Benchmark (length) Mode Cnt Score Error Units

[info] alternatives.algebird.StringItemBenchmark.algebirdGet 1024 thrpt 20 1181080.172 ▒ 9867.840 ops/s

[info] alternatives.algebird.StringItemBenchmark.algebirdPut 1024 thrpt 20 157158.453 ▒ 844.623 ops/s

[info] alternatives.breeze.StringItemBenchmark.breezeGet 1024 thrpt 20 5113222.168 ▒ 47005.466 ops/s

[info] alternatives.breeze.StringItemBenchmark.breezePut 1024 thrpt 20 4482377.337 ▒ 19971.209 ops/s

[info] alternatives.guava.StringItemBenchmark.guavaGet 1024 thrpt 20 5712237.339 ▒ 115453.495 ops/s

[info] alternatives.guava.StringItemBenchmark.guavaPut 1024 thrpt 20 5621712.282 ▒ 307133.297 ops/s

// My Bloom filter

[info] bloomfilter.mutable.StringItemBenchmark.myGet 1024 thrpt 20 11483828.730 ▒ 342980.166 ops/s

[info] bloomfilter.mutable.StringItemBenchmark.myPut 1024 thrpt 20 11634399.272 ▒ 45645.105 ops/s

[info] bloomfilter.mutable._128bit.StringItemBenchmark.myGet 1024 thrpt 20 11119086.965 ▒ 43696.519 ops/s

[info] bloomfilter.mutable._128bit.StringItemBenchmark.myPut 1024 thrpt 20 11303765.075 ▒ 52581.059 ops/s

Basically, this implementation is 2x faster than Google’s Guava and 10-80x than Twitter’s Algebird. Other benchmarks you can find in the “benchmarks’ module on github

Warning: These are synthetic benchmarks in isolated environment. Usually the difference in throughput and latency is bigger in production system because it will stress the GC, lead to slow allocation paths and higher latencies, trigger the GC, etc.

Where to use?

High performance and low latency systems.

Big Data and Machine learning systems with a lot of data and billions of unique elements.

When not to use it:

You are ok with your current solution. Most software don’t have to be fast.

You trust only proven and battle-tested libraries from famous companies like Google or Twitter.

You want it to work out-of-the-box.

What’s next?

Feedback is welcome and appreciated. The next step will be to implement the Stable Bloom filter data structure because there’s no good implementation. I plan to do some experiments with the Cuckoo filer data structure. Any experience so far?

Thank you!

Leave a Comment