.NET Generics under the hood

Note: This post is based on the talk I gave at a .NET meetup. You can find the slides here.

Overview

Compare with Java and C++Short intro- Generics in .NET

- .NET object memory layout

- .NET Generics under the hood

- The dessert - a bug in JITter

- Moral

Intro

I was going to start with a comparison to Java “generics” and C++ templates just to show that .NET is “better”. But I decided not to do that because we already know that .NET is wonderful. Don’t we? So let’s leave it as a statement ![]() We will recall .NET’s object memory layout and how objects lay in memory and about

We will recall .NET’s object memory layout and how objects lay in memory and about Method Table and EEClass. We will take a look at how Generics affect them and how they work under the hood, and what optimizations CLR performs to keep them efficient. Then there’s a dessert prepared about performance degradation and a bug in CLR. Stay tuned ![]()

Yes, Java and a couple of swear words. When I was developing for .NET, I always thought that it’d be cool somewhere else, in another world, stack or language. That everything would be interesting and easy there. Hey, Scala has pattern matching, they shouted. Once we introduce Kafka, we can process millions of events easily. Or Akka Streams, that’s a bleeding edge and would solve all our stream processing problems. And interest took root and I moved to JVM. And more than half a year I write code in Scala. I noticed that I have started to curse more often, I don’t sleep well, and I come home and cry on my pillow sometimes. I don’t have accustomed things and tools anymore that I had in .NET. And Generics of course which don’t exist in JVM ![]() People here in Lithuania say:

People here in Lithuania say: "Šuo ir kariamas pripranta." That means a dog can even get used to the gallows. I have started to like it but that’s another story. Sooo…

Generics in .NET

And they are awesome! Probably there are no developers who don’t use them or love them. Are there any? They have a lot of advantages and benefits. In the CLR documentation, it’s written that they make programming easier, yes it’s bold there. They reduce code duplication. They are smart and support constraints such as class and struct, and implements classes and interfaces. They can preserve inheritance through covariance and contravariance. They improve performance: no more boxings/unboxings, no castings. And all that happens during compilation. How cool is that?! But nothing is free and we’ll figure out the price ![]()

.NET memory layout

First, let’s recall how objects are stored in memory. When we create an instance of an object, then the following structure (array) is allocated in the heap:

var o = new object();

+----------------------+

| An instance |

+----------------------+

| Header |

| Method Table address |

| Field1 |

| FieldN |

+----------------------+

The first element is called the “header” and contains a hashcode or an address in the lock table. The second element contains the Method Table address. Next are the fields of the object. So, the variable o is just a pointer that points to the Method Table. And the Method Table is …

EEClass

Let me start from EEClass ![]()

EEClass is a class, and it knows everything about the type it represents. It gives access to its data through getter and setters. It’s quite a complex class. It consists of more than 2000 lines of code and contains other classes and structs, which are also not so small. For example, there is EEClassOptionalFields, which is like a dictionary that stores optional data. Or EEClassPackedFields, which optimizes memory use. EEClass stores a lot of numeric data, such as the number of methods, fields, static methods, static fields, etc. So, EEClassPackedFields optimizes them, drops leading zeros and packs them into one array with access by index. EEClass is also called “cold data”. So, getting back to Method Table.

Method Table

Method Table is used for optimization! Everything that the runtime needs is extracted from EEClass to Method Table. It’s an array with access by index. It is also called “hot data”. It may contain the following data:

+-------------------------------------+

| Method Table |

+-------------------------------------+

| EEClass address |

| Interface Map Table address |

| Inherited Virtual Method addresses |

| Introduced Virtual Method addresses |

| Instance Method addresses |

| Static Method addresses |

| Static Fields values |

| InterfaceN method addresses |

+-------------------------------------+

WinDbg

To take a look at how they are presented in CLR, WinDbg comes to the rescue - the great and powerful. It’s a very powerful tool for debugging any application running on Windows but it has an awful user interface and user experience ![]() There are plugins:

There are plugins: SOS (Son of Strike) from the CLR team and SOSex from a third-party developer.

The Son of Strike isn’t just a nice name. When the CLR team was formed, it had an informal name “Lightning”. They created a tool for debugging the runtime and called it “Strike”. It was a very powerful tool that could probably do everything in CLR. When the time came for the first release, they limited it and called “Son of Strike”. True story ![]()

POCO example

Let’s take a simple class:

public class MyClass

{

private int _myField;

public int MyMethod()

{

return _myField;

}

}

It has a field and a method. If we create an instance of it and take a dump of the memory then we will see our object there:

var myClass = new MyClass();

0:003> !DumpHeap -type GenericsUnderTheHood.MyClass

Address MT Size

0000004a2d912de8 00007fff8e7540d8 24

Statistics:

MT Count TotalSize Class Name

00007fff8e7540d8 1 24 GenericsUnderTheHood.MyClass

Total 1 objects

and its Method Table:

0:003> !dumpmt -md 00007fff8e7540d8

EEClass: 00007fff8e8623f0

Module: 00007fff8e752fc8

Name: GenericsUnderTheHood.MyClass

mdToken: 0000000002000002

File: C:\Projects\my\GenericsUnderTheHood\GenericsUnderTheHood\bin\Debug\GenericsUnderTheHood.exe

BaseSize: 0x18

ComponentSize: 0x0

Slots in VTable: 6

Number of IFaces in IFaceMap: 0

--------------------------------------

MethodDesc Table

Entry MethodDesc JIT Name

00007fffecc86300 00007fffec8380e8 PreJIT System.Object.ToString()

00007fffeccce760 00007fffec8380f0 PreJIT System.Object.Equals(System.Object)

00007fffeccd1ad0 00007fffec838118 PreJIT System.Object.GetHashCode()

00007fffeccceb50 00007fffec838130 PreJIT System.Object.Finalize()

00007fff8e8701c0 00007fff8e7540d0 JIT GenericsUnderTheHood.MyClass..ctor()

00007fff8e75c048 00007fff8e7540c0 NONE GenericsUnderTheHood.MyClass.MyMethod()

We can see its name, some statistics and a table of methods. WinDbg/SOS has a problem: it doesn’t show all the information but shows additional data from other sources. And the EEClass:

0:003> !DumpClass 00007fff8e8623f0

Class Name: GenericsUnderTheHood.MyClass

mdToken: 0000000002000002

File: C:\Projects\my\GenericsUnderTheHood\GenericsUnderTheHood\bin\Debug\GenericsUnderTheHood.exe

Parent Class: 00007fffec824908

Module: 00007fff8e752fc8

Method Table: 00007fff8e7540d8

Vtable Slots: 4

Total Method Slots: 5

Class Attributes: 100001

Transparency: Critical

NumInstanceFields: 1

NumStaticFields: 0

MT Field Offset Type VT Attr Value Name

00007fffecf03980 4000001 8 System.Int32 1 instance _myField

Links to dig deeper

I find the “.NET Type Internals” article on codeproject quite comprehensive. And I liked the “Pro .NET Performance” book by Sasha Goldshtein, Dima Zurbalev and Ido Flatow. It has a really good chapter about type internals.

To get familiar with WinDbg, I recommend the “Debugging .NET with WinDbg” tutorial by Sebastian Solnica

Generics under the hood

Generic class example

Let’s take a look at how Generics affect our Method Tables and EEClasses. A simple generic class:

public class MyGenericClass<T>

{

private T _myField;

public T MyMethod()

{

return _myField;

}

}

After compilation, we get the following IL code:

.class public auto ansi beforefieldinit

GenericsUnderTheHood.MyGenericClass`1<T>

extends [mscorlib]System.Object

{

.field private !T _myField

.method public hidebysig

instance !T MyMethod () cil managed

{

...

}

...

}

The name has the type arity “`1” showing the number of Generic type parameters and !T as a placeholder for the type. It’s a template that tells JIT that the type is generic and unknown at the compile time and will be defined later. Miracle! ![]() CLR knows about Generics

CLR knows about Generics ![]() Let’s create an instance of our generic with type

Let’s create an instance of our generic with type object and take a look at the Method Table:

var myObject = new MyGenericClass<object>();

0:003> !DumpMT -md 00007fff8e754368

EEClass: 00007fff8e862510

Module: 00007fff8e752fc8

Name: GenericsUnderTheHood.MyGenericClass`1[[System.Object, mscorlib]]

mdToken: 0000000002000003

File: C:\Projects\my\GenericsUnderTheHood\GenericsUnderTheHood\bin\Debug\GenericsUnderTheHood.exe

BaseSize: 0x18

ComponentSize: 0x0

Slots in VTable: 6

Number of IFaces in IFaceMap: 0

--------------------------------------

MethodDesc Table

Entry MethodDesc JIT Name

00007fffecc86300 00007fffec8380e8 PreJIT System.Object.ToString()

00007fffeccce760 00007fffec8380f0 PreJIT System.Object.Equals(System.Object)

00007fffeccd1ad0 00007fffec838118 PreJIT System.Object.GetHashCode()

00007fffeccceb50 00007fffec838130 PreJIT System.Object.Finalize()

00007fff8e870210 00007fff8e754280 JIT GenericsUnderTheHood.MyGenericClass`1[[System.__Canon, mscorlib]]..ctor()

00007fff8e75c098 00007fff8e754278 NONE GenericsUnderTheHood.MyGenericClass`1[[System.__Canon, mscorlib]].MyMethod()

The name has a System.Object parameter type but its methods have a strange signature. Mystic System.__Canon has appeared. The EEClass:

0:003> !DumpClass 00007fff8e862510

Class Name: GenericsUnderTheHood.MyGenericClass`1[[System.__Canon, mscorlib]]

mdToken: 0000000002000003

File: C:\Projects\my\GenericsUnderTheHood\GenericsUnderTheHood\bin\Debug\GenericsUnderTheHood.exe

Parent Class: 00007fffec824908

Module: 00007fff8e752fc8

Method Table: 00007fff8e7542a0

Vtable Slots: 4

Total Method Slots: 6

Class Attributes: 100001

Transparency: Critical

NumInstanceFields: 1

NumStaticFields: 0

MT Field Offset Type VT Attr Value Name

00007fffecf05c80 4000002 8 System.__Canon 0 instance _myField

The name with the same mystic System.__Canon and type of field is also System.__Canon. Let’s create an instance with the string type:

var myString = new MyGenericClass<string>();

0:003> !DumpMT -md 00007fff8e754400

EEClass: 00007fff8e862510

Module: 00007fff8e752fc8

Name: GenericsUnderTheHood.MyGenericClass`1[[System.String, mscorlib]]

mdToken: 0000000002000003

File: C:\Projects\my\GenericsUnderTheHood\GenericsUnderTheHood\bin\Debug\GenericsUnderTheHood.exe

BaseSize: 0x18

ComponentSize: 0x0

Slots in VTable: 6

Number of IFaces in IFaceMap: 0

--------------------------------------

MethodDesc Table

Entry MethodDesc JIT Name

00007fffecc86300 00007fffec8380e8 PreJIT System.Object.ToString()

00007fffeccce760 00007fffec8380f0 PreJIT System.Object.Equals(System.Object)

00007fffeccd1ad0 00007fffec838118 PreJIT System.Object.GetHashCode()

00007fffeccceb50 00007fffec838130 PreJIT System.Object.Finalize()

00007fff8e870210 00007fff8e754280 JIT GenericsUnderTheHood.MyGenericClass`1[[System.__Canon, mscorlib]]..ctor()

00007fff8e75c098 00007fff8e754278 NONE GenericsUnderTheHood.MyGenericClass`1[[System.__Canon, mscorlib]].MyMethod()

The name with string type but methods have the same strange signature with System.__Canon. If we take a closer look, then we’ll see that addresses are the same as in the previous example with the object type. So, the EEClass is the same for a string typed generic and it’s shared with object typed generic. However, their Method Tables are different. Let’s take a look at value types:

var myInt = new MyGenericClass<int>();

0:003> !DumpMT -md 00007fff8e7544c0

EEClass: 00007fff8e862628

Module: 00007fff8e752fc8

Name: GenericsUnderTheHood.MyGenericClass`1[[System.Int32, mscorlib]]

mdToken: 0000000002000003

File: C:\Projects\my\GenericsUnderTheHood\GenericsUnderTheHood\bin\Debug\GenericsUnderTheHood.exe

BaseSize: 0x18

ComponentSize: 0x0

Slots in VTable: 6

Number of IFaces in IFaceMap: 0

--------------------------------------

MethodDesc Table

Entry MethodDesc JIT Name

00007fffecc86300 00007fffec8380e8 PreJIT System.Object.ToString()

00007fffeccce760 00007fffec8380f0 PreJIT System.Object.Equals(System.Object)

00007fffeccd1ad0 00007fffec838118 PreJIT System.Object.GetHashCode()

00007fffeccceb50 00007fffec838130 PreJIT System.Object.Finalize()

00007fff8e870260 00007fff8e7544b8 JIT GenericsUnderTheHood.MyGenericClass`1[[System.Int32, mscorlib]]..ctor()

00007fff8e75c0c0 00007fff8e7544b0 NONE GenericsUnderTheHood.MyGenericClass`1[[System.Int32, mscorlib]].MyMethod()

The name with the System.Int32 type, signatures have it too. The EEClass is typed with System.Int32 too.

0:003> !DumpClass 00007fff8e862628

Class Name: GenericsUnderTheHood.MyGenericClass`1[[System.Int32, mscorlib]]

mdToken: 0000000002000003

File: C:\Projects\my\GenericsUnderTheHood\GenericsUnderTheHood\bin\Debug\GenericsUnderTheHood.exe

Parent Class: 00007fffec824908

Module: 00007fff8e752fc8

Method Table: 00007fff8e7544c0

Vtable Slots: 4

Total Method Slots: 6

Class Attributes: 100001

Transparency: Critical

NumInstanceFields: 1

NumStaticFields: 0

MT Field Offset Type VT Attr Value Name

00007fffecf03980 4000002 8 System.Int32 1 instance _myField

So how does it work under the hood then?

Value types do not share anything and each value type has its own Method Table and EEClass and its own JITted code. In other words, for each value type used as a generic type parameter, CLR will produce a different piece of code. This could lead to what is known as “code bloat” or code explosion and increase the memory footprint of the program. But that’s inevitable because the compiler has to know the size of the value type and the layout of its fields during the compilation process.

Reference types have their own Method Tables. And we can say that a Method Table uniquely describes a type. But all reference types of a generic share one EEClass and share JITted code of its methods between each other. In other words, for each reference type used as a generic type parameter, CLR will use one piece code. That’s an optimization for the memory that greatly reduces the footprint used for Generics. That’s possible because reference types have the same “word” size. System.__Canon is an internal type and acts as a placeholder. Its main goal is to tell JIT that the type will be found during runtime.

The rules are the same for generics with more than one type parameter. If all type parameters are reference types, then code is shared otherwise not.

Everything is pretty straightforward when you call a specialized(typed) generic method from a regular method. All checks and type lookups can be done during the compilation (inc JIT) phase. But things get tricky when you call a generic method from another generic method where you don’t know the type. The code for the reference types is shared, remember? When a shared method is executed then any application of generics in its body will have to be looked up to get the concrete runtime type. CLR calls this process “runtime handle lookup”. This process is the most important aspect of making shared generic code as nearly as efficient as regular methods. Because of the critical performance needs of this feature, both the JIT and runtime cooperate through a series of sophisticated techniques to reduce the overhead.

Let’s talk about how the runtime optimizes these lookups. There are essentially a series of caches to avoid the ultimately expensive lookup of types at runtime via the class loader. Without going into too much detail, you can abstractly look at the lookup costs like this:

- “Class loader” - This walks through the entire hierarchy of objects and their methods and tries to find out which method fits the application. Obviously, this is the slowest way to do it. (300 clocks)

- Type hierarchy walk with global cache lookup - This is a hierarchy walk but it looks in the global cache using the declaring type. (think about 50-60 clocks for a hit)

- Global cache lookup - This is a lookup in the global cache using the current and the declaring type. (think about 30 clocks for a hit)

-

Method Tableslot - This adds a slot to the declaring type with a code sequence that can lookup the exact type within a few levels of indirection (think 10 clocks for a hit).

The source for this info is given a bit later.

The dessert

This is the most interesting part for me. I work on high-load low latency and other fancy-schmancy systems. At that time, I worked on a real-time bidding system that handled ~500K RPS with latencies below 5ms. After some changes, we encountered a performance degradation in one of our modules that parsed the user-agent header and extracted some data from it. I have simplified the code as much as I can to reproduce the issue:

public class BaseClass<T>

{

private List<T> _list = new List<T>();

public BaseClass()

{

Enumerable.Empty<T>();

// or Enumerable.Repeat(new T(), 10);

// or even new T();

// or foreach (var item in _list) {}

}

public void Run()

{

for (var i = 0; i < 8000000; i++)

{

if (_list.Any())

// or if (_list.Count() > 0)

// or if (_list.FirstOrDefault() != null)

// or if (_list.SingleOrDefault() != null)

// or other IEnumerable<T> method

{

return;

}

}

}

}

public class DerivedClass : BaseClass<object>

{

}

We have a generic class BaseClass<T>, which has a generic field and a method Run to perform some logic. In the constructor, we call a generic method and in method Run() too. And we have an empty class DerivedClass, which is inherited from the BaseClass<T>. And a benchmark:

public class Program

{

public static void Main()

{

Measure(new DerivedClass());

Measure(new BaseClass<object>());

}

private static void Measure(BaseClass<object> baseClass)

{

var sw = Stopwatch.StartNew();

baseClass.Run();

sw.Stop();

Console.WriteLine(sw.ElapsedMilliseconds);

}

}

The empty DerivedClass is 3.5 times slower. Can you explain it?? ![]()

I asked a question on SO. A lot of developers appeared and started to teach me how to write benchmarks ![]() Meanwhile, on RSDN, an interesting workaround was found saying “just add two empty methods”:

Meanwhile, on RSDN, an interesting workaround was found saying “just add two empty methods”:

public class BaseClass<T>

{

...

public void Method1()

{

}

public void Method2()

{

}

...

}

My first thoughts were like WAT?? What programming is that when you add two empty methods and it performs faster?? Then I got an answer from Microsoft with the same workaround and saying that the reason is due to the JIT heuristic algorithm. I felt relieved. No more magic there. Then, the CLR sources were opened and I raised an issue on GitHub. I got a really great explanation from @cmckinsey one of CLR’s engineers/managers, who explained everything in detail and admitted that it’s a bug in JITter. Go and read it! It’s worth it. I’ll wait.

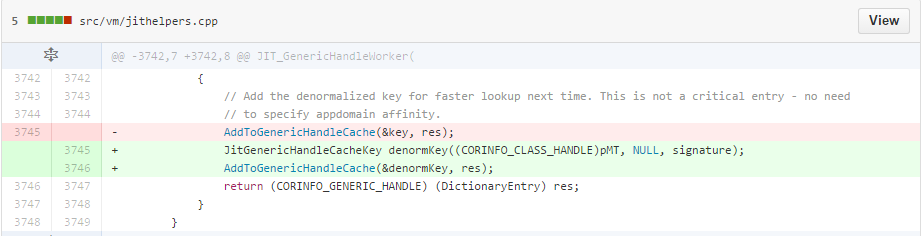

And after all that digging, here’s the fix:

Basically, it says that point #3 “Global cache lookup” in the list of optimizations mentioned above doesn’t work as expected (or at all). Take a look at the comment above the changed lines - it wasn’t changed because it was right. That rare moment… ![]()

Moral

Is your code slow? Just add two empty methods ![]() Everyone experiences this bug for, probably, years. It has been fixed in .NET Core only so far. I just was lucky to find it, and I asked and pushed the CLR team to fix it. Actually, .NET Framework is being developed by engineers like you and me. They also make bugs. And that’s normal. Just for fun. If there wasn’t any interest then nothing would happen.

Everyone experiences this bug for, probably, years. It has been fixed in .NET Core only so far. I just was lucky to find it, and I asked and pushed the CLR team to fix it. Actually, .NET Framework is being developed by engineers like you and me. They also make bugs. And that’s normal. Just for fun. If there wasn’t any interest then nothing would happen.

Leave a Comment